There's this thing that happens every time I'm here, one of the things I most look forward to: I re-learn my place in the universe.

Idaho is vast and as varied as the snowflakes which are currently falling outside. My family lives in the southeast corner of the state, where deserts meet mountains. Our valley, the Portneuf, is the place where two ranges come together. The northern part of the city opens up onto sage-scrubbed, volcanic plains, but down here, in the south, everything gets squeezed together into a tight little gap, through which the Portneuf River runs. We are surrounded on all sides by mountains-tall hills, really––which are covered in juniper and more sage, some of it taller and wider than my car. I can leave and drive up the hills to an isolated place that overlooks everything, surrounded by pine and aspen, quakies and cedar. Or I can turn in the other direction and find myself in vast emptiess, the mountains distant bumps on the horizon, with only the sound of the wind, or the occasional grumble of trucks on the interstate to remind me that I exist at all. Idaho's landscape changes constantly and it's one of the things I love most about it.

But nothing compares to Idaho's skies. Montana is the "Big Sky" state, and they do give good firmament there, but I have to say (and perhaps I'm a bit partial) Idaho's skies are spectacular beyond anything I've seen in the Absarokas, or from the Big Horns. I have stood in the Tetons and gazed upward. I have perched on the edge of the Grand Canyon. I have floated in the Gulf of Mexico and watched the sunset, but I remember those skies only as setting, backdrop full of color and emotion and little more.

I have spent entire afternoons with friends sprawled on our backs watching clouds roll overhead. One memorable day at the end of high school my friend Ruth and I couldn't tear our eyes away from a cloud shaped like a falling man. Every few seconds his arms would shift, his hands reach out for something-anything-to grasp ahold of, until after fifteen minutes he'd actually turned from his back onto his belly, his head pointed down at the hill below him, his hair and shirttails flapping behind him. I have watched cloud dogs chase cloud rabbits and then witnessed those rabbits turn into airplanes that chased the dogs. I have seen the sunsets mottled with balls of gold and purple fire that burned away the blue and painted everything as far as I could see in deep crimson.

But as beautiful as the days are, the nights are even better. There is always a moment when I stand on the hill behind my mother's house and gaze upward at a night sky so deep and clear that it's like a scene from a movie. Picture a close-up of my face and then the camera slowly pulls back until you can see all of me against stone and yellow grass and sage, and it keeps pulling back until you can't differentiate me from a clump of juniper. It pulls back more and you can see the whole hill, then the valley and the city, then the city becomes a mass of orange lights, then a single glow amid vast darkness dotted by other orange pools. It keeps moving, faster and faster until the whole planet is in view and then the moon slips by and stars flitter past and you're looking at earth, a tiny glittering dot, as seen from the Big Dipper. It keeps racing away until finally there is only darkness that magically pulls out from the pupil of my eye and you see my face again.

That is how night feels in Idaho, bigger than the words that describe it or the pictures that can be taken of it. It's a moment I cherish and I always feel as though my knees will give out from under me and I'll be forced to the earth by the weight of infinity. It sucks the breath out of my lungs and I can only marvel, mute and deaf, unaware of any sense except vision.

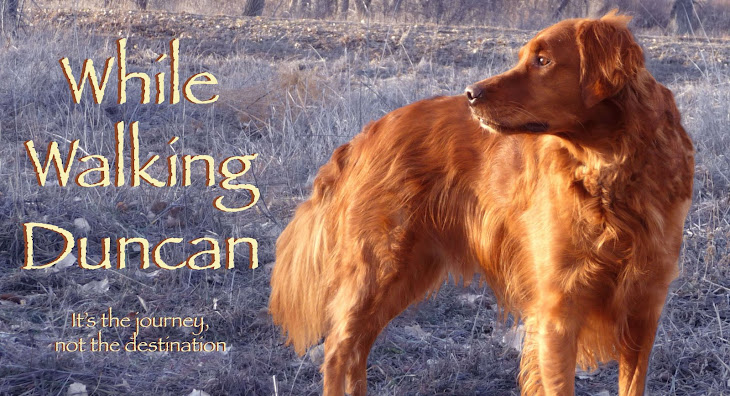

Duncan was with me last night on the hill when it happened again. He was busy sniffing out a clump of sage while I staggered and shook my head on my backward-craned neck. He did not care, because for him all that mattered was being outside and pushing his nose through the snow, over shale and thistle.

All that mattered to me was that I was there, with him at my side under that glorious Christmas night sky.

Idaho is vast and as varied as the snowflakes which are currently falling outside. My family lives in the southeast corner of the state, where deserts meet mountains. Our valley, the Portneuf, is the place where two ranges come together. The northern part of the city opens up onto sage-scrubbed, volcanic plains, but down here, in the south, everything gets squeezed together into a tight little gap, through which the Portneuf River runs. We are surrounded on all sides by mountains-tall hills, really––which are covered in juniper and more sage, some of it taller and wider than my car. I can leave and drive up the hills to an isolated place that overlooks everything, surrounded by pine and aspen, quakies and cedar. Or I can turn in the other direction and find myself in vast emptiess, the mountains distant bumps on the horizon, with only the sound of the wind, or the occasional grumble of trucks on the interstate to remind me that I exist at all. Idaho's landscape changes constantly and it's one of the things I love most about it.

But nothing compares to Idaho's skies. Montana is the "Big Sky" state, and they do give good firmament there, but I have to say (and perhaps I'm a bit partial) Idaho's skies are spectacular beyond anything I've seen in the Absarokas, or from the Big Horns. I have stood in the Tetons and gazed upward. I have perched on the edge of the Grand Canyon. I have floated in the Gulf of Mexico and watched the sunset, but I remember those skies only as setting, backdrop full of color and emotion and little more.

I have spent entire afternoons with friends sprawled on our backs watching clouds roll overhead. One memorable day at the end of high school my friend Ruth and I couldn't tear our eyes away from a cloud shaped like a falling man. Every few seconds his arms would shift, his hands reach out for something-anything-to grasp ahold of, until after fifteen minutes he'd actually turned from his back onto his belly, his head pointed down at the hill below him, his hair and shirttails flapping behind him. I have watched cloud dogs chase cloud rabbits and then witnessed those rabbits turn into airplanes that chased the dogs. I have seen the sunsets mottled with balls of gold and purple fire that burned away the blue and painted everything as far as I could see in deep crimson.

But as beautiful as the days are, the nights are even better. There is always a moment when I stand on the hill behind my mother's house and gaze upward at a night sky so deep and clear that it's like a scene from a movie. Picture a close-up of my face and then the camera slowly pulls back until you can see all of me against stone and yellow grass and sage, and it keeps pulling back until you can't differentiate me from a clump of juniper. It pulls back more and you can see the whole hill, then the valley and the city, then the city becomes a mass of orange lights, then a single glow amid vast darkness dotted by other orange pools. It keeps moving, faster and faster until the whole planet is in view and then the moon slips by and stars flitter past and you're looking at earth, a tiny glittering dot, as seen from the Big Dipper. It keeps racing away until finally there is only darkness that magically pulls out from the pupil of my eye and you see my face again.

That is how night feels in Idaho, bigger than the words that describe it or the pictures that can be taken of it. It's a moment I cherish and I always feel as though my knees will give out from under me and I'll be forced to the earth by the weight of infinity. It sucks the breath out of my lungs and I can only marvel, mute and deaf, unaware of any sense except vision.

Duncan was with me last night on the hill when it happened again. He was busy sniffing out a clump of sage while I staggered and shook my head on my backward-craned neck. He did not care, because for him all that mattered was being outside and pushing his nose through the snow, over shale and thistle.

All that mattered to me was that I was there, with him at my side under that glorious Christmas night sky.

1 comment:

I have no memory of that. Do you realize that you serve as a faithful steward of my past?

Post a Comment