And did you feel it, in your heart, how it pertained to everything?

And have you too finally figured out what beauty is for?

And have you changed your life? (Mary Oliver)

The grass is golden and tall, reaching nearly to my hip, and in some places where perhaps water has pooled and trickled through shallow channels, it rises even taller, to the middle of my chest, reaching with spindly fingers to the soft place just beneath my arms where it hopes to coax and tickle a smile from my lips. But I am not smiling, not entirely, only the smile of one who walks with his face pointed directly into the sun, squinted and necessary, almost uncomfortable were it not for the joy of the heat kissing my cheeks and lips. The sky is blue, cool and frosty, not Summerish in its delight, but tinted and artificial, distant, something that clings, like dust motes in the thick air of a tightly cluttered space. My hands are flat out at my sides and my passing stirs the long grass around me, the tall blades reach up to brush against the flat warm terrain of my palms, a map of valleys and canyons, wide plains, forgotten winding paths that end subtly, vanishing as the last song on an album fades further and deeper into silence. There is a soft wind, and although the field around me stirs and undulates, rising and falling in wide waves, there is no sound, just the sound of my feet on the earth and my breath in my ears. My pocket is heavy and deep with a few of the things I hold most precious. When I reach into it my fingers are able to discern the names of the things without pulling them free for my eyes to dance across: the sound of a flock of night-flying geese skimming the upper surface of a low cloud beneath which I stand, the silver shimmer of mist caught in low clumps of wet morning grass, the fat round face of a full moon peeking through the clouds on the eastern horizon, the spearmint and perfume scent of my grandmother's purse, a photo of Ken's shadow-dappled face taken on the bank of the river up Boulder Canyon, the color of my mother's yard under the Christmas lights, the rabid laughter of Kevi when she's on a roll and the gentle

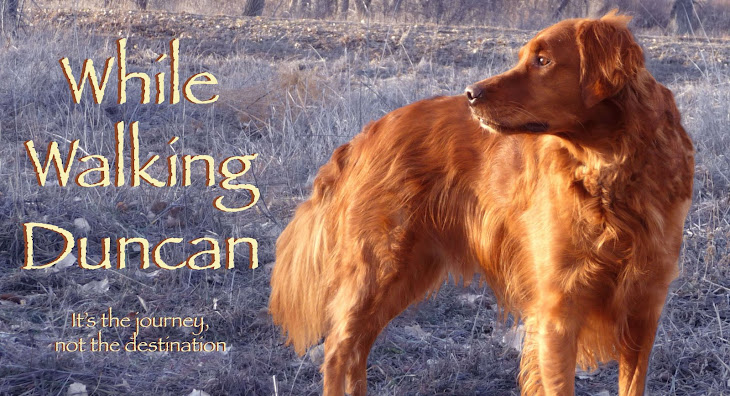

hmmmm of Ruth when she listens to me talk of fears and sadness, every word written by Mary Oliver, the steps of the kittens when they climb onto my back, turn in a circle and settle down in tight little balls between my shoulder blades. The other pocket is empty so there is plenty of room for the scent of the Linden and Russian Olive trees, the bounce of the road on my bike ride to work, the feeling of Ken's hand in mine, the bubbled laughter and songs of the children I may or may not get to have, shooting stars and the wishes bound to them. When my fingers fumble in all that empty space my pace quickens, the walk becomes a jog and then a crouching run and from somewhere close by I hear a steady rush, movement through the grass, which seems to whisper my location and give me away. I smile and run harder, one hand clutching the pocket, careful to keep the call of the geese safely tucked inside. I stumble but the grass catches me, is cool against my face, a thousand tiny fingers massaging my scalp, the back of my arms, stealing peeks down my collar. The rushing is close, coming faster and I give up crawling and hiding and roll onto my back, the blue of the air obscured by the gold of the grass, and then Duncan has found me, his tongue big and pink, his eyes brown and joyous as they push through the field, dragging the rest of him behind. He sees me, does that little leap of his where his front feet leave the ground for only a moment, as if dancing, and then falls onto my chest, the long red hair at his neck pushing into my face, his scent filling my nostrils, the cold of his nose a chill across my neck into my ear.

And as the dream ends I think,

there are many things I want, and may even need, but for now I am content in the love of such a good dog.

1 comment:

I remember the wonders of a field like that from my childhood. We used to let the field between our house and my Grandma's grow up, and we would build mazes of "rooms" of mashed-down grass, which had been as tall as our heads, connected by trails. We were always admonished not to do that, as the tractor's cutting bar couldn't cut hay that was not standing up. We didn't care.

Post a Comment